This week I was asked to help prepare artwork for a commercial print job. The job involves a die-cut template to be used for packaging across a range of products, for which there are some 40 different variants.

The customer supplied an individual block of information for each product, which needed to be merged with the template. This wouldn’t have been too complicated except these blocks weren’t supplied in a nice convenient PDF with one page per block, and everything in the same position: oh, no – the blocks were supplied as A4 pages, several to a page.

Needless to say, I was keen to avoid manually cropping out and placing 40 individual blocks – partly because it’s tedious, but also because it’s error-prone.

At this point you might be wondering where’s the “retro” angle in this sorry little tale…

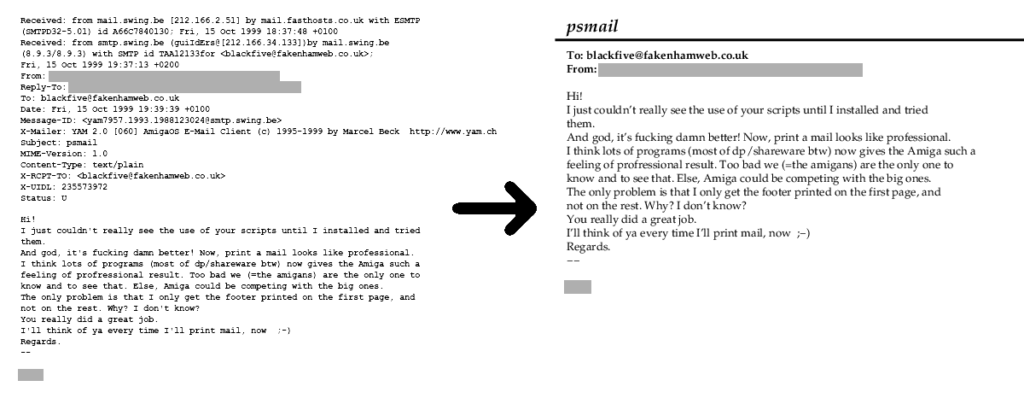

Cast your mind back to the late 1990s. The Amiga is all but dead as a commercial platform but a number of us, including myself, still used it on a daily basis. Even after buying a PC, I continued to use the YAM email client under WinUAE for several years, since I was comfortable with it, and all my existing emails and contacts were already there. In fact, I remained with YAM up until Thunderbird came along.

YAM was an excellent piece of software but it had one major shortcoming compared with PC mail clients: printed emails looked awful. When you asked YAM to print an email it would just hurl ASCII text at the printer, so your expensive Canon Bubblejet or Epson Stylus printer would end up spitting out a sheet of ugly monospaced draft-quality text more befitting of the late 80s than the turn of the millennium.

Round about that time I’d been experimenting with Ghostscript, the Postscript interpreter. I ended up writing some scripts for YAM which would flow and word-wrap raw text from an email into nicely formatted pages, and then run those through Ghostscript to print them.

Postscript-based workflows are very much a thing of a past now, supplanted almost entirely by PDF – but there are still occasions where Postscript is useful; for instance, I often export in EPS format from Inkscape, because then I can easily edit the generated file in a text editor to ensure the colours are in CMYK with the exact values I want (without a round-trip to sRGB and back messing with them), or even change them to spot colour – things that still can’t be done natively in Inkscape.

So going back to my print job project, someone younger than me would probably be looking at Python or Javascript, and trying to find a reliable and battle-tested PDF library capable of cropping and resizing PDFs without mangling anything in the process.

Instead, I went oldskool – I used Ghostscript to manipulate the pages, and wrote a simple Postscript program to isolate the individual blocks.

When being interpreted in an environment which has filesystem access (as opposed to being interpreted on a printer), a Postscript program can call EPS files (and, for that matter, regular Postscript files and – with Ghostscript – even PDFs) just by doing “(//path//to//file.eps) run”. Because EPS files won’t (shouldn’t!) mess with the page setup, will (should!) draw relative to the current graphics context, and won’t (shouldn’t!) call “showpage” it’s very easy to set up a page and then place a graphic from an EPS file just by embedding it, or calling it with the run command. Further, it’s easy to set up a clipping region so that only part of an EPS will be visible.

So the first point of order is to convert the customer-supplied PDF to a bunch of EPS files, which can be done using “-sDEVICE=epswrite -sOutputFile=/path/to/filename%d.eps” as command-line options to Ghostscript. (The %d in the output filename is important: it instructs Ghostscript to create a separate file for every page. Without that, it would try to put all pages in the same file, which meaningless for a single-page format like EPS.)

Having collected a bunch of EPS files, the next step is to extract the individual blocks from them. My Postscript program to achieve this was as follows:

/mm {72 mul 25.4 div} def

%% define dimensions of the labels

/width 80 mm def

/height 17 mm def

/PlaceEPS %% filename PlaceEPS -

{

gsave

/epsdict 200 dict def %% Create a dictionary for the EPS to use

epsdict begin

/showpage {} def %% override showpage in case a bad EPS calls it.

run

{

currentdict epsdict eq end %% clean up any dictionaries left behind

{ exit } if

}

loop

grestore

} def

/dofile {

/fn exch def

<< /PageSize [width height] >> setpagedevice

/i 0 def

{

i 5 gt { exit } if %% run the loop six times, with i = 0 through 5

%% set up a clipping region

newpath

0 0 moveto

width mm 0 mm lineto

width mm height mm lineto

0 mm height mm lineto

eoclip

%% shift the page horizontally by 75mm, and vertically by

%% 243mm - i * 45mm, so that each label in turn

%% appears within the clipping region

75 mm neg 243 i 45 mul sub mm neg translate

%% Page the EPS file

fn PlaceEPS

showpage

/i i 1 add def

} loop

} def

(//path//to//file_1.eps) dofile

(//path//to//file_2.eps) dofile

...I ran this program using Ghostscript with the “pdfwrite” device, and ended up with a 42-page PDF with each product’s information block in the same position, suitable for merging with the template.